Aloe vera and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: Views from Preliminary Studies

Hashimoto's thyroiditis, the most prevalent form of hypothyroidism, is characterised by autoimmune attacks on the thyroid gland, predominantly affecting women aged 30-50. In this condition, antibodies produced by the immune system target and permanently damage the thyroid, often leading to a gradual decline in thyroid function.

While traditional treatment involves lifelong thyroid hormone replacement, recent studies, such as one from Messina, Italy, suggest a potential alternative involving Aloe barbendensis Miller juice (ABMJ).

Aloe Vera: A Medicinal Plant

Aloe vera, scientifically known as Aloe barbendensis Miller, has historical use in both medicine and food. Widely acknowledged for its topical safety, caution is necessary when ingesting aloe due to the potential intestinal irritation caused by aloin-containing latex.

Aloe Barbadensis leaf juice is derived from the leaves of the aloe plant, containing a rich array of over 200 nutritional substances. Among these are 20 minerals, including iron, chromium, zinc, selenium, copper, manganese, magnesium, sodium, potassium, and calcium. Additionally, Aloe Barbadensis leaves contain 20 (out of the 21) amino acids, a dozen vitamins (A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B12, C, E, choline, and folic acid), and active enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase, amylase, bradykinase, carboxypeptidase, catalase, cellulase, lipase, and peroxidase.

Notably, Aloe Barbadensis leaves contain the rare amino acid tyrosine, crucial in thyroid hormone formation, with arginine being the predominant amino acid. The presence of anthraquinones, sterols (campesterol, β-sitosterol, lupeol), lignin, saponins, and salicylic acids contributes to the diverse properties of Aloe vera.

The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory attributes of Aloe vera are attributed to vitamins A, C, and E, the glycoprotein C-glucosyl chromone, specific sterols, plant hormones (auxins and gibberellins), and bradykinase. Moreover, campesterol, β-sitosterol, lupeol, aloin, and emodin within Aloe Barbadensis act as analgesics and antiseptics, resembling compounds found in shea butter and sabal/saw palmetto (Serenoa repens).

Preliminary Studies

The small-scale Italian study involved thirty women with subclinical hypothyroidism from Hashimoto's thyroiditis, who consumed ABMJ daily for nine months. The study’s limitations include the absence of a placebo control group and inconsistencies in the reported dosage of ABMJ. However, the observed improvements in thyroid indices and antithyroid antibody levels are intriguing.

Another study demonstrated that A. vera may regulate thyroid function to maintain a constant level of thyroid hormones in the body, and could be a candidate for thyroid disease therapies. (Ryuk, JA. Hiro, G. Byoung-Seob, K. (2022)

Participant and Study Protocol

Thirty women, aged 20 to 55, with Hashimoto's thyroiditis participated in the study. All had elevated serum thyroperoxidase autoantibodies (TPOAb) levels. The study excluded individuals with other diseases or those using nutraceuticals/drugs affecting the thyroid. Participants were instructed to consume 50-100 ml of ABMJ each morning on an empty stomach.

Despite the promising results, the study emphasises the need for clarity regarding the dosage, highlighting a serious flaw in the research.

Thyroid Hormones

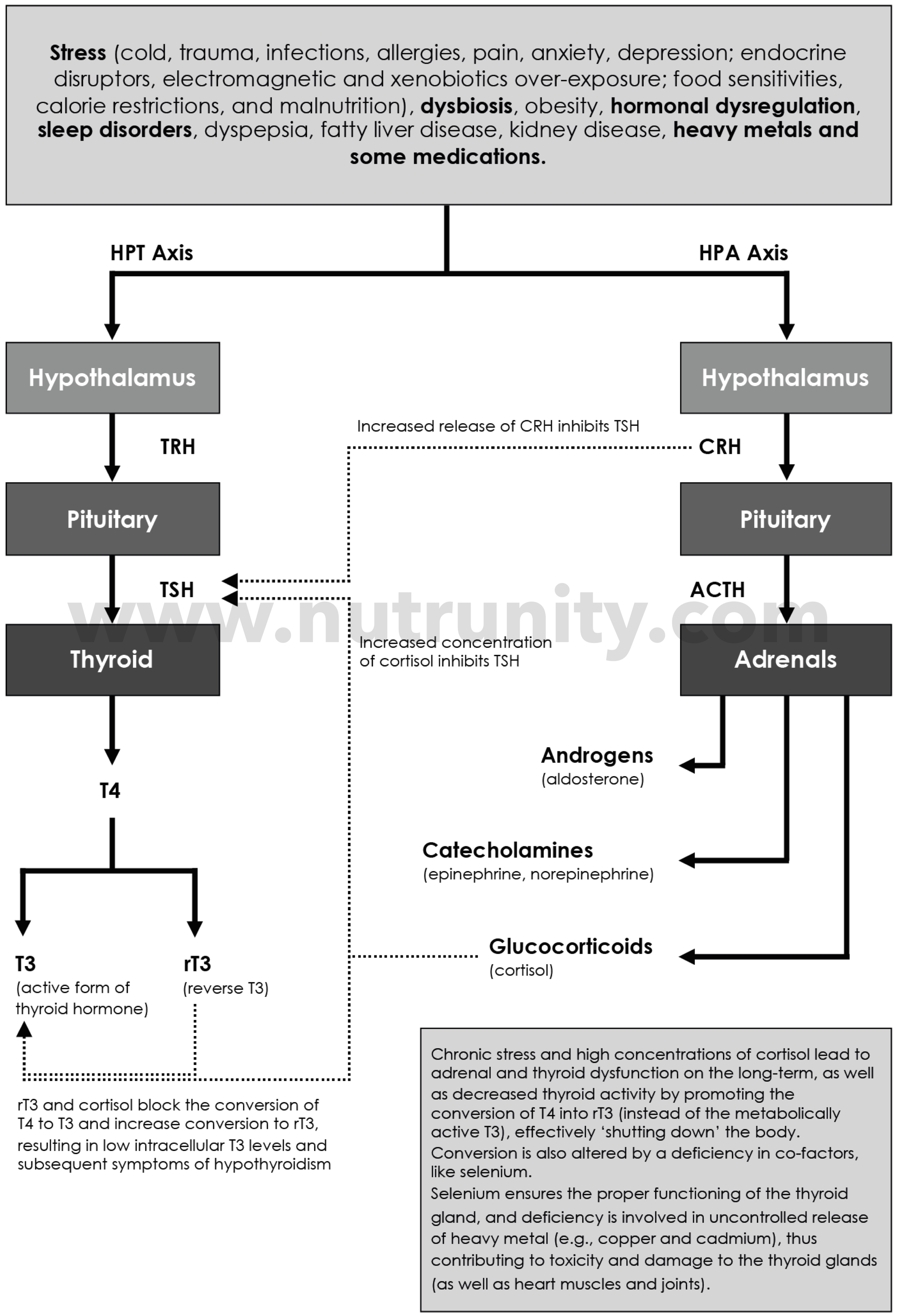

Thyroid hormones play a crucial role in the normal growth and development. The intricate regulation of their production and release involves a feedback loop system, which includes the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary gland, and thyroid. The process begins with the hypothalamus releasing thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), stimulating the pituitary gland to produce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH, in turn, prompts the thyroid gland to produce thyroid hormones. This intricate system operates within a negative feedback loop to inhibit the release of both TRH and TSH when thyroid hormone levels are elevated. Such regulation ensures a constant level of thyroid hormones in the body, preventing the onset of hypo- and hyperthyroidism, indicating insufficient or excessive thyroid hormone production, respectively.

Thyroid hormone pathways and causes of dysfunction. Illustration by Olivier Sanchez, extracted from “Energise - 30 Days to Vitality.”

Results

Despite limitations, the study demonstrated marked improvements in thyroid status and TPOAb levels after nine months (improvements were already measured after three months). Notably, all thirty women exhibited normalised thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels, with some achieving even better reductions. Similar improvements were observed in free thyroxine (FT4) levels and antibody levels — At baseline, 100% of women had TSH > 4.0 mU/L and TPOAb > 400 U/ml, but frequencies fell to 0% and 37%, respectively, at month 9. However, clinical parameters like goitre size, body weight, and other laboratory data were not addressed.

A. vera contains several bioactive compounds, such as vitamins, minerals, sugars, and enzymes, giving it nutritional and therapeutic properties and beneficial effects, including anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, antibacterial effects, and regulation of intestinal function. Therefore, it is already used to treat constipation, skin disease, infections, diabetes, and gastrointestinal disorders, among several other conditions

The most recent study concluded that A. vera can be used to treat hypothyroidism due to its ability to increase TPO protein expression. The ability of A. vera to increase TPO could be induced by the inhibition of TPO autoantibodies. Thyroid peroxidase could be a key factor in A. vera-regulated thyroxine release and the presence of tyrosine, the main constituent of the thyroid hormone, in Aloe barbadensis leaves, could be one of the reasons for its curative effects on hypothyroidism.

Safety Considerations

The study reported no side effects during the nine months, but the lack of details on side-effect assessment and the absence of a placebo group raises concerns. Safety information, including potential interactions with medications, remains inadequately addressed. While cautiously optimistic about the preliminary findings, the study emphasises the necessity for randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials to establish the efficacy and safety of aloe in managing Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

According to Drugs.com, no interactions were found between aloe vera and levothyroxine. Since A. vera is shown to combat free radicals and thus displays anti-inflammatory properties, it may be an adjunct to treatment for maximum effect.

Additional studies should be done to confirm the efficacy of Aloe Vera juice, but these preliminary findings are promising. There are not very many substances currently that can lower antibodies for Hashimoto’s this quickly. There is extensive research on selenomethionine (selenium) and its efficacy in lowering antibodies. Protocols combining Aloe vera and selenium may provide greater support for autoimmune thyroiditis.

It is highly recommended to consult your health practitioner and be supervised when supplementing long-term with pure Aloe vera juice (aloin-free and latex-free products). It is also essential to address blood sugar and lipid dysfunction and inflammation (low-grade or systemic), incorporate stress-reducing methods, detect food intolerances and allergies, and restore gut integrity and gut microbial diversity.

References:

Metro, D. Cernaro, V. Papa, M. et al. (2018). Marked improvement of thyroid function and autoimmunity by Aloe barbadensis miller juice in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Journal of Clinical and Translational Endocrinology. 11, pp. 18-25. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2018.01.003

Ryuk, JA. Hiro, G. Byoung-Seob, K. (2022). Effects of Aloe vera on the regulation of thyroxine release in FRTL-5 thyroid cells. Applied Sciences. 12(23), 11919. doi:10.3390/app122311919

Rieu, M. Richard, A. Rosilio, M. et al. (1994). Effects of thyroid status on thyroid autoimmunity expression in euthyroid and hypothyroid patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Clinical Endocrinololgy (Oxford). 40(4), pp/ 529-535. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02494.x