Artificially-sweetened and Sugary Drinks, and Ultra‑Processed Foods: From Liver Disease to Neurodegeneration

Most people still think of liver disease and dementia as completely separate problems: one driven by alcohol, the other by age or “bad luck.” In reality, ultra‑processed manufactured food products and sugary drinks are quietly linking metabolic dysfunction, fatty liver, neuroinflammation and cognitive decline through a shared gut–liver–brain axis.

What you eat and drink each day is not just shaping your waistline and liver health, it’s also shaping your microbiome, impacting your inflammatory load and, over time, the health of your brain.

Ultra‑Processed Foods, Metabolic Syndrome and Fatty Liver

Ultra‑processed food products (UPFs), packaged products high in refined starches, added sugars, cheap fats, salt and additives, now account for a large share of daily calories in Europe and the UK, especially among younger people. Observational studies and meta‑analyses show a clear association between higher UPF intake and:

Metabolic syndrome (central obesity, high blood pressure, elevated triglycerides, low HDL, impaired fasting glucose).

Type 2 diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia, known risk factors for MASLD (metabolic dysfunction‑associated steatotic liver disease).

UPFs promote metabolic dysfunction through several converging mechanisms:

Poor nutrient profile: energy dense, low in fibre, micronutrients and protective phytochemicals, promoting weight gain, insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia.

Refined carbohydrates and added sugars: rapid post‑prandial glucose and insulin spikes, driving lipogenesis and visceral fat accumulation.

Industrial fats: high saturated and trans‑like fats aggravate insulin resistance and ectopic fat deposition in the liver and skeletal muscle.

Food additives and emulsifiers: experimental work links certain emulsifiers, colourants and sweeteners to gut barrier disruption and dysbiosis, increasing systemic inflammation.

Given that MASLD is defined by liver fat in the presence of metabolic risk factors, it is not surprising that diets dominated by UPFs and sugary drinks are consistently associated with higher MASLD and NAFLD prevalence.

“Detox before Energise” explains in great detail the impact of excessive sugar intake on liver disease. Here is an extract:

“Gut dysbiosis, obesity, and metabolic disorders have been linked to liver inflammation, which contributes to systemic, low-grade inflammation.

Cases of liver disease, such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and a large spectrum of liver lesions occurring in the context of obesity, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome are also increasing. It is estimated that 25% of American adults and 20% of UK adults have NAFLD.

Approximately a quarter of the global population is predicted to be living with NAFLD, a disease which can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer, with the prevalence increasing alongside the increase in obesity.

A diet rich in refined and ultra-processed sugars, coupled with the consumption of hydrogenated and trans-fats, alongside a sedentary lifestyle, stands as a prominent contributor to gut dysbiosis, increased gut permeability (leaky gut syndrome), systemic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, type-2 diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and the presence of endotoxins. These endotoxins are well-known for their role in causing liver inflammation and, therefore, NAFLD.”

From NAFLD to MASLD: Why the Liver Is Now a Metabolic Warning Light

Historically, NAFLD (non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease) was diagnosed in someone who did not drink or consumed very little alcohol. As the contributing metabolic factors became clearer, experts proposed MASLD (metabolic dysfunction‑associated steatotic liver disease) to emphasise that this is a metabolic liver disease, not simply “fat in the liver by accident.”

To be diagnosed, MASLD requires:

Evidence of hepatic steatosis (on imaging, biopsy or biomarkers), plus

At least one metabolic risk factor: visceral obesity, prediabetes/diabetes, raised triglycerides, low HDL, or elevated blood pressure.

MASLD now affects a substantial proportion of adults globally and is tightly linked to obesity, metabolic syndrome and ultra‑processed, sugar‑rich dietary patterns.

MASLD increases the risk of:

• Steatohepatitis (inflammatory fatty liver), fibrosis and cirrhosis.

• Hepatocellular carcinoma and liver‑related mortality.

• Cardiovascular events, which remain the leading cause of death in people with MASLD.

Importantly, MASLD is also increasingly recognised as a neurological risk factor, via vascular damage, chronic inflammation and direct effects on the brain, via the liver–brain axis.

Whichever name is used, NAFLD or MASLD, the core problem is the same: fat and inflammation slowly build up inside the liver, increasing the risk of cirrhosis, liver cancer, and cardiovascular disease over time.

Sugary Drinks, Fructose and De Novo Lipogenesis in the Liver

Among UPFs, sugar‑sweetened beverages (and even “diet” drinks) stand out as particularly harmful for liver health. Large cohorts, including the UK Biobank, have shown:

Drinking more than 330ml per day (one can) of sugary or low/non‑sugar‑sweetened drinks is associated with a substantially higher risk of MASLD, even after adjusting for confounders.

Excessive intake of high-sugar-sweetened beverages is linked to a 47% higher risk of MASLD; high intake of low‑/non‑sugar‑sweetened drinks is linked to a 60% higher risk.

Sugary drink consumption is associated with higher liver cancer incidence and chronic liver disease mortality in long‑term cohorts.

Mechanistically, this is driven largely by fructose metabolism:

Sucrose and high‑fructose corn syrup provide both glucose and fructose. Glucose raises blood sugar and insulin; fructose is taken up primarily by the liver and, in high doses, is rapidly channelled into de novo lipogenesis (DNL) – the synthesis of new fat from carbohydrate (leading to fat accumulation in the liver as well).

Fructose upregulates lipogenic transcription factors (SREBP‑1c, ChREBP) and enzymes (acetyl‑CoA carboxylase, fatty acid synthase), markedly increasing hepatic triglyceride production.

Excess fructose also depletes ATP, increases uric acid and compromises mitochondrial oxidation, fuelling oxidative stress (tissue damage) and inflammatory signalling in the liver.

Human studies show people with NAFLD often consume significantly more fructose, mainly from sugary drinks, than matched controls; fructose restriction reduces liver fat, DNL and improves insulin function.

By contrast, fructose from whole fruit, delivered with fibre and polyphenols, does not appear to confer the same hepatic risk and is often associated with better cardiometabolic profiles. It is easier to drink a full glass of orange juice with added corn syrup than to eat the six-to-eight oranges required to make the juice. Why is high-fructose corn syrup added to already sweetened juices, even some labelled freshly squeezed? Because sugar is addictive, and by drinking those drinks regularly, you destroy your taste buds, so healthy foods taste bland, and all you want is more sugar and more addictive UPFs.

Ultra‑Processed Diets, Gut Dysbiosis and the Gut–Liver Axis

UPFs and sugary drinks do not act in isolation. They remodel the gut microbiome, thin the intestinal barrier, and create a pro‑inflammatory milieu that flows directly to the liver via the portal vein – the gut–liver axis.

Key features include:

Dysbiosis:

Diets high in refined carbohydrates, emulsifiers and low in fibre reduce beneficial SCFA‑producing bacteria and favour the growth of opportunistic species.

Increased intestinal permeability:

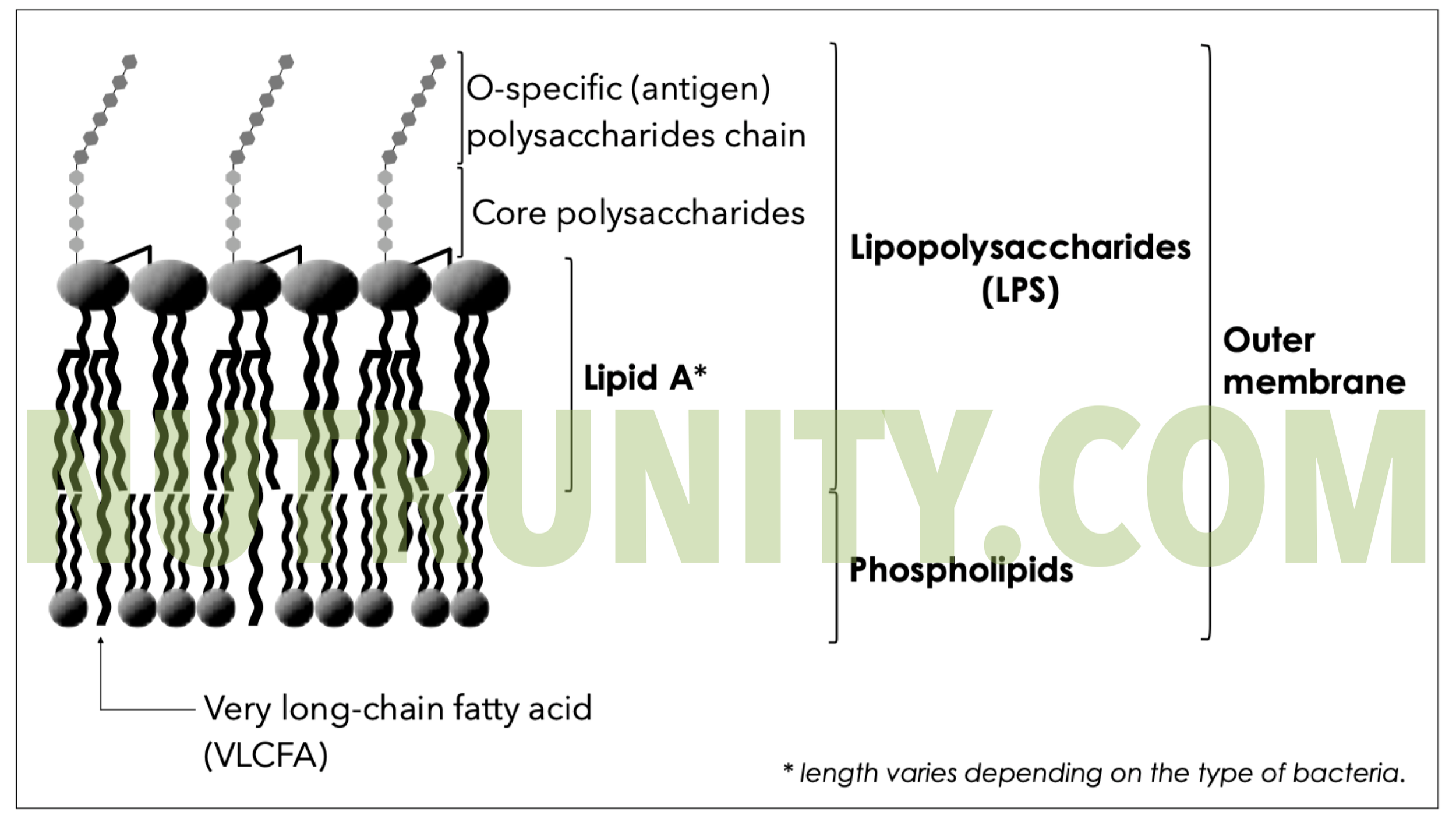

Tight-junction disruption allows the passage of bacterial products, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), into the circulation.

Endotoxemia and hepatic inflammation:

LPS and other microbial molecules activate Kupffer cells in the liver, promoting inflammatory cascades, oxidative stress and fibrogenesis – all central to MASLD and alcohol‑associated liver disease.

Remarkably, some NAFLD patients harbour high‑alcohol–producing strains, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae that can ferment dietary carbohydrates into substantial quantities of ethanol (up to 1 litre of 6% alcohol beer a day), causing liver lesions that resemble alcoholic liver disease despite little or no alcohol intake. Animal models show that colonisation with such strains can reproduce fatty liver and inflammation, confirming how profoundly the microbiome can modulate dietary risk.

Thus, ultra‑processed, sugar‑rich diets damage the liver via calories and fructose, as well as by reprogramming the microbiome into a more toxic, alcohol‑producing, barrier‑disrupting ecosystem.

Gram-negative Bacterial Membrane with LPS, including Lipid A, the most toxic component. Illustration extracted from “Detox before Energise.” All rights reserved.

From Liver Inflammation to Neuroinflammation: The Liver–Brain Axis

The traditional “gut–brain axis” concept has now expanded into a gut microbiota-gut–liver–brain axis, with MASLD as a central hub. Several mechanistic threads connect fatty liver to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration:

Systemic low‑grade inflammation:

MASLD and metabolic syndrome are characterised by chronically elevated inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. These cytokines can cross or compromise the blood–brain barrier (BBB), activate microglia and astrocytes, and promote neuroinflammatory cascades linked to cognitive decline and mood disorders.

Vascular injury and small vessel disease:

NAFLD shares risk factors with atherosclerosis and is associated with arterial stiffness, carotid atherosclerosis, and cerebral small-vessel disease. This vascular pathology contributes to vascular dementia, white matter changes and executive dysfunction.

Direct brain structural changes:

Mendelian randomisation data suggest that NAFLD is causally linked to changes in cortical structures and reduced global cortical surface area, providing genetic‑level support for a liver–brain axis.

Ammonia and neurotoxic metabolites:

Even before overt cirrhosis, impaired hepatic detoxification can allow accumulation of ammonia and other metabolites that affect neurotransmission and astrocytic function, contributing to subtle cognitive impairment.

Clinical studies now consistently show:

Higher dementia risk in NAFLD: large cohort data report that NAFLD is associated with increased risk of all‑cause dementia, particularly vascular dementia, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

Cognitive impairment in NAFLD: prospective studies find that 12–41% of NAFLD patients exhibit measurable deficits in attention, executive function and psychomotor speed, with liver fibrosis associated with worse performance on inhibitory control tasks.

In essence, the same ultra‑processed, sugar‑heavy diet that drives metabolic syndrome and MASLD is also laying down the conditions for neuroinflammation, vascular injury and cognitive decline via this integrated liver–brain axis.

Ultra‑Processed Foods and Neuroinflammation: Beyond the Liver

Separate from liver pathology, UPFs also act directly on the gut–brain axis:

Diets high in refined carbs, added sugars and saturated fats are repeatedly linked to neuroinflammation and reduced cognitive function in both animal and human studies.

UPFs reduce the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, which are essential for maintaining BBB integrity and modulating microglial activation.

Overconsumption of UPFs has been associated with higher depression risk, altered reward pathways and potential damage to dopamine‑producing neurons, suggesting that the inflammatory and metabolic burden of these foods extends into mood and motivation circuits. Once again, linking UPFs to over-consumption of highly addictive UPFs via dopamine reward pathways.

A recent narrative review concluded there is a strong association between UPF intake, disrupted lipid metabolism and increased risk of mental disorders, even in populations without overt metabolic disease.

When the same diet simultaneously drives metabolic inflammation, fatty liver and neuroinflammation, the cumulative risk for neurodegenerative disease and dementia becomes difficult to ignore. It is not surprising that Alzheimer’s dementia is quickly becoming one of the greatest killers today.

How to Protect the Liver–Brain Axis in an Ultra‑Processed World

From a clinical and public‑health standpoint, the priorities are straightforward, even if implementation is challenging. The aim is to lower ultra‑processed load, reduce liquid sugars, restore gut integrity and support metabolic flexibility.

1. Cut liquid sugar and high‑volume sweeteners first

Phase down daily soft drinks, energy drinks, sweetened coffees and large fruit drinks – even “diet” versions.

Replace with water, herbal infusions, unsweetened coffee/tea or sparkling water with citrus; these swaps alone can reduce MASLD risk in cohort data.

2. De‑ultra‑process your baseline diet

Prioritise minimally processed foods: vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, plus quality fats and proteins.

Reserve UPFs (crisps, packaged sweets, fast food, ready meals) for occasional use rather than as daily staples. Use the rule of 4. For every cheat meal or snack, cook four meals from scratch or using minimally processed whole foods.

3. Feed your microbiome, seal the gut barrier

Aim for a diversity of plant fibres to support SCFA‑producing bacteria and maintain gut barrier integrity, reducing LPS‑mediated liver and brain inflammation.

Dietary (prebiotic) fibre, fermented foods (if well tolerated) and, where appropriate, evidence‑based probiotics can support a healthier gut ecosystem, particularly in those with dysbiosis or frequent antibiotic exposure.

4. Target metabolic resilience

Emphasise daily movement, including resistance and aerobic training, to improve insulin sensitivity and help clear hepatic fat.

Ensure adequate sleep and stress management; both are strongly linked to metabolic risk, appetite regulation and inflammatory tone.

5. Screen, monitor and intervene early

In patients with obesity, type 2 diabetes, or high UPF intake, consider screening for MASLD using liver enzymes, fibrosis scores, and imaging, where indicated.

In established MASLD, remain alert to subtle cognitive changes and cardiovascular comorbidities; the evidence now supports viewing MASLD as a multi‑organ risk state rather than a liver‑only condition.

When you put this together, a clear picture emerges: ultra‑processed foods and sugary drinks are not just empty calories. They are active drivers of metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, gut dysbiosis, neuroinflammation and, ultimately, increased dementia risk via an integrated gut–liver–brain axis.

Helping patients and the public understand this connection and providing realistic steps to lower UPFs, protect the liver, and support the microbiome is now central to any serious strategy for preventing both metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases.

References

Arab, JP., Arrese, M., Shah, VH. (2020). Gut microbiota in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcohol-related liver disease: Current concepts and perspectives. Hepatology Research. 50(4), pp. 407-418. doi:10.1111/hepr.13473

Callingham, F. (2024). The UK city ‘so unhealthy’ one in every four locals are addicted to fizzy drinks. Available at: https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/health/1868319/uk-city-addicted-fizzy-drinks. [Accessed: 10 Feb. 2026]

Cassidy, YJ., Chen, C., Cui, J. et al. (2019). Fatty liver disease caused by high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metabolism. 30(4), pp. 675-688.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.018

Chen, H., Wang, J., Li, Z. et al. (2019). Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages has a dose-dependent effect on the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An updated systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16(12), 2192. doi:10.3390/ijerph16122192

Denova-Gutiérrez, E., Rivera-Paredez, B., Quezada-Sánchez, AD. et al. (2025). Soft drink consumption and increased risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Results from the health workers cohort study. Annals of Hepatology. 30(1), 101566. doi:10.1016/j.aohep.2024.101566

Fackelmann, G., Manghi, P., Carlino, N. et al. (2025). Gut microbiome signatures of vegan, vegetarian and omnivore diets and associated health outcomes across 21,561 individuals. Nature Microbiology. 10, pp. 41–52 doi:10.1038/s41564-024-01870-z

Fairfield, B., Schnabl, B. (2020). Gut dysbiosis as a driver in alcohol-induced liver injury. JHEP Reports. 3(2), 100220. doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100220

Formisano, A., Dello Russo, M., Lissner, L. et al. (2025). Ultra-processed foods consumption and metabolic syndrome in European children, adolescents, and adults: Results from the I.Family Study. Nutrients. 17(13), 2252. doi:10.3390/nu17132252

Geidl-Flueck, B., Gerber, PA. (2023). Fructose drives de novo lipogenesis affecting metabolic health. Journal of Endocrinology. 257(2), e220270. doi:10.1530/JOE-22-0270

Godsey, TJ., Eden, T., Emerson, SR. et al. (2025). Ultra-processed foods and metabolic dysfunction: A narrative review of dietary processing, behavioral drivers and chronic disease risk. Metabolites. 15(12), 784. doi:10.3390/metabo15120784

Herman, MA., Samuel, VT. (2016). The sweet path to metabolic demise: Fructose and lipid synthesis. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 27(10), pp. 719-730. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2016.06.005

Kjærgaard, K., Mikkelsen, ACD., Wernberg, CW. et al. (2021). Cognitive dysfunction in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Current knowledge, mechanisms, and perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10(4), 673. doi:10.3390/jcm10040673

Kirpich, IA., Parajuli, D., McClain, CJ. (2015). Microbiome in NAFLD and ALD. Clinical Liver Disease (Hoboken). 6(3), pp. 55-58. doi:10.1002/cld.494

Le, P., Tatar, M., Dasarathy, S. et al. (2025). Estimated burden of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in US adults, 2020 to 2050. JAMA Network Open. 8(1), e2454707. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.54707

Liu, L., et al. Sugar- and low/non-sugar-sweetened beverages and risks of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and liver-related mortality: A prospective analysis of the UK Biobank. Abstract OP161. UEG Week 2025, 4-7th October 2025.

Martínez Leo, EE., Segura Campos, MR. (2020). Effect of ultra-processed diet on gut microbiota and thus its role in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrition. 71, 110609. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2019.110609

Medina-Julio, D., Ramírez-Mejía, MM., Córdova-Gallardo, J. et al. (2024). From liver to brain: How MAFLD/MASLD impacts cognitive function. Medical Science Monitor. 30, e943417. doi:10.12659/MSM.943417

Meijnikman, AS., Davids, M., Herrema, H. et al. (2022). Microbiome-derived ethanol in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nature Medicine. 28(10), pp. 2100-2106. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02016-6

NHS (2022). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/non-alcoholic-fatty-liver-disease [Accessed: 10 Feb. 2026]

Ouyang, X., Cirillo, P., Sautin, Y. et al. (2008). Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Hepatology. 48(6), pp. 993-999. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.011

Poon, E., Li, C., Schweitzer, D., et al. (2026). Neurobiological insights into the effects of ultra-processed food on lipid metabolism and associated mental health conditions: a scoping review. Frontiers in Nutrition. 12, 1754492. doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1754492

Sanchez, O. (2021). Energise - 30 Days to Vitality. Nutrunity Publishing. London. Available at: https://amzn.eu/d/09KdSaZp

Sanchez, O. (2021). Liver dysfunction. Detox before Energise.Nutrunity Publishing. London. Available at: https://amzn.eu/d/0bi5sPIW

Sanchez, O. (2025). The Serious Health Implications of Fructose. Available at: https://www.nutrunity.com/updates/fructose-health-effects. [Accessed: 10 Feb. 2026]

Shang, Y., Widman, L., Hagström, H. (2022). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of dementia: A population-based cohort study. Neurology. 99(6), e574-e582. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200853

Shu, L., Zhang, X., Zhou, J. et al. (2023). Ultra-processed food consumption and increased risk of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Frontiers in Nutrition. 10, 1211797. doi:10.3389/fnut.2023.1211797

Sidhu, SRK., Kok, CW., Kunasegaran, T. et al. (2023). Effect of plant-based diets on gut microbiota: A systematic review of interventional studies. Nutrients. 15(6), 1510. doi:10.3390/nu15061510

Softic, S., Cohen, DE., Kahn, CR. (2016). Role of dietary fructose and hepatic de novo lipogenesis in fatty liver disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 61(5), pp. 1282-1293. doi:10.1007/s10620-016-4054-0

Sun, Y., Yu, B., Wang, Y. et al. (2023). Associations of sugar-sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and pure fruit juice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Endocrine Practice. 29(9), pp. 735-742. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2023.06.002

Wu, SY., Bo, YC., Li, ZY. et al. (2025). EAT-Lancet diet and risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and other liver chronic diseases: A large prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Frontiers in Nutrition. 12, 1589424. doi:10.3389/fnut.2025.1589424

Younossi, ZM., Golabi, P., Price, JK. et al. (2024). The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among patients with type 2 diabetes. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 22(10), pp. 1999-2010.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2024.03.006

Younossi, ZM., Kalligeros, M., Henry, L. et al. (2025). Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology. 31, S32-S50. doi:10.3350/cmh.2024.0431

Zakir-Hussain, M. (2025). Liver disease warning issued over ingredients found in ‘diet’ drinks. The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/diet-drinks-artificial-sweeteners-liver-disease-warning-ssbs-b2841445.html [Accessed 10 Feb. 2026]

Zhao, L., Zhang, X., Coday, M. et al. (2023). Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Liver Cancer and Chronic Liver Disease Mortality. JAMA. 2023 Aug 8;330(6):537-546. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.12618. PMID: 37552302; PMCID: PMC10410478.

Zhu, L., Baker, RD., Zhu, R. et al. (2016). Gut microbiota produce alcohol and contribute to NAFLD. Gut. 65(7), 1232. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311571